|

|

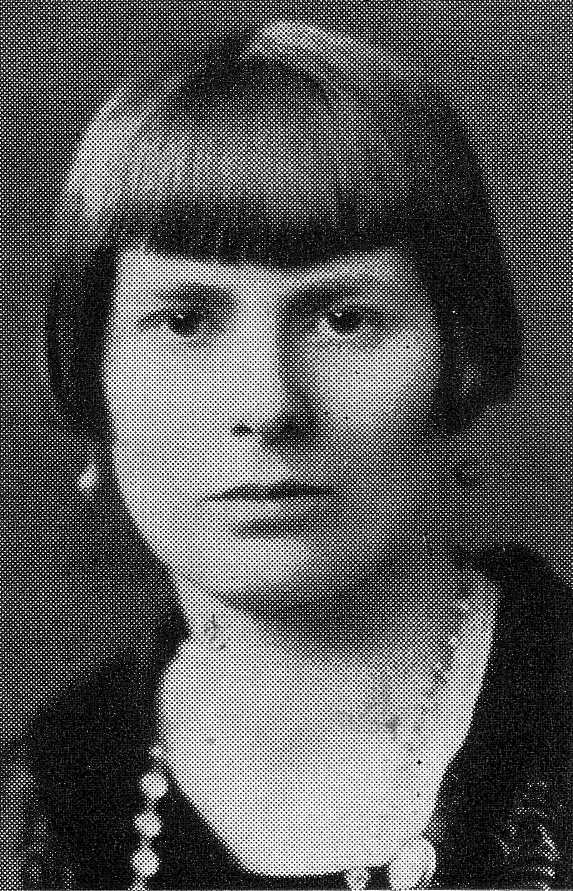

Barbara Barclay Carter

|

THE OTHER DAY I turned up an

old exercise-book belonging to my twelfth year, and was amused

to find an essay: "How I would earn my living if I had to,"

(the conditional clause representing a polite fiction, current

till well beyond the end of the last war, that "nice"

little girls did not expect to earn their livings as a matter

of course). It is a business-like account of how a large fortune

could be amassed by breeding dogs, but at the end comes the revealing

after-thought: "If I did not breed dogs I might breed cats

or be a writer." I remember still the uncomfortable feeling

that all that had gone before was insincere and worthless; it

was on writing that my will was fixed, as it had long been. I

had written almost as soon as I could form my letters, first

pocms (in the childhood of the individual as of the peoples,

verse-forms come before prose), then tales, and finally a "novel"

of fifty whole foolscap pages, all of them carefully preserved

by maternal pride. But how could eleven-years-old explain that

inner compulsion- or how it could be turned to the earning of

a living? It was simpler to talk about dogs. . . .

We were then living in Richmond,

a few miles from London. Of Santa Barbara, California, where

I was born, I have alas! no direct memory, for my Anglo-Irish

mother brought me to England before I was two years old. Only

through her eyes and those of my much loved Welsh nurse, who

came back with her, could I see the sun-lit orange-trees, the

glittering blue of the Pacific, the sheer rise of the great mountains,

but so vivid were their pictures that they form part of the texture

of my childhood. I was not allowed to forget that I was an American.

One day, when I was very small, an American flag appeared unexpectedly

in a little shop in our neighborhood, and my oId nurse led me

to it with real excitement, "Kiss it, baby," she said,

"That's the Star Spangled Banner. It's your flag."

For many years after, it hung over my cot.

So, too, when I began to appreciate

poetry, my mother would read to me for preference from an American

anthology - Little Orphan Annie, and Paul Revere's Ride, and

the Battle Hymn of the Republic. I soon knew by heart, though

in regard to the last she woula impress upon me that since my

father came from Georgia I must not identify myself with the

cause of the North. Though living in England, my "second

country" was not England but Wales - my oId nurse's land,

whither she took me for holidays that were the highlights of

each year, to share the life of her kin-her brother the blacksmith,

her sister-in-law who kept a baker's shop, her innumerable cousins

who farmed the rich, mountain-guarded lands of the Usk valley,

till I grew as passionately attached to the land itself as if

it had been my own. Of all this I have written in Old Nurse.

By a coincidence, one of the reviewers of my earlier book on

Dante, Ship Without Sails, had to deal at the same time

with two books on Wales, and bridged the transition by saying:

"It is a very long way from twentieth century Wales to the

fourteenth century Florence of Miss Barclay Carter's book."

Actually, it was through the intense local attachment of the

Welsh and the spell of Wales that I was able to understand the

aching nostalgia for Florence of the exile whom an American writer

has described as "the most homesick man in this home-sick

world."

My school was run by an able

Swiss woman, so that we specialised in French. It was thus that

my first appearance in print (otherwise than in the school magazine,

where I wrote under the pseudonym of "Californian Poppy")

was what may be by courtesy be called a French poem in honour

of King Albert of Belgium, in L'Independance Belge, which

was published in London during the last war. I was then fourteen.

The war ended soon after I had left school for a secretarial

training college. Many of us who had grown up with the thought

of war-service as soon as we were of age for it, felt the need

to find some other high cause to claim our allegiance. I found

it in insurgent Ireland. The seeds had been sown by the parish

priest in Wales, where, after my mother's death, my oId nurse's

house seemed my real , home. Acquaintance with the poems of Pearse

and Plunkett and MacDonagh ripened them. Had not my own grand-father

been an Irishman? (That he, poor man, an Anglican Bishop of Jerusalem

and a strong conservative, might well have turned in his grave

at the thought of a Sinn Feiner grand-daughter was no matter.)

I joined the Gaelic League, started learning Irish, and, under

the inspiration of the Celtic Twilight wrote two short stories

set in the Ireland I had never seen, with sufficient verisimilitude

to win publication in Irish papers. This was the first money

I earned by my pen-something to tell in triumph to my aunts in

England, my guardian in America, who had even fewer illusions

than myself at eleven on writing as a means of earning a living.

I felt I had made a beginning, Unfortunately, however, I have

never been one of those who are able to write at odd moments,

in time squeezed from other work. And I felt more and more that

for such writing as should be mine I needed the university training

that had been denied me.

For three years I did secretarial

work-in London, in Geneva with the International Labour Office,

and with the Irish Legation in Rome. In the meantime, on a visit

to my ever-dear old nurse in 1921, I had been received into the

Catholic Church. (The parish-priest had sown other seeds than

those of Sinn Fein, but my decision-at Geneva, of all places-had

a far earlier impulse at its origin, for my mother had had a

great reverence for Catholicism and had shown clearly a wish

to encourage me in a direction she herself shrank from taking

as a forsaking of the church of her fathers.)

Then, I was twenty-one. I came

into what seemed the large sum of a hundred and fifty pounds

($750). I took it to go to Paris, to study at the Sorbonne. 'With

a Faustian thirst for knowledge for its own sake, rejecting all

utilitarian considerations, I proclaimed grandiloquently that

I wished simply to "apprendre pour comprendre," and

for the four courses requisite for a degree chose Mediaeval History,

History of Art, Ancient History, and French Literature. To these

I added Italian Literature, for already Dante exercised on me

a supreme attraction. For a year, too, I studied Scholastic Philosophy

at the Catholic Institute.

I had taken the cheapest room

that I could find, on the seventh floor of the Hotel Lhomond,

behind the Pantheon, cooking my own meals-into which that friend

of man, the horse entered largely--on a spirit stove. Even with

such strict economy, my $750 would not have lasted long, had

not Providence taken a hand. The hostel of the Catholic Institute

gave yearly scholarships to Irish and American students. The

Directress - she was a nun of the order of St. Ursula, though

this was kept an open secret since the laws against religious

congregations were still nominally in force - gave me one of

the American scholarships one year, and an Irish one the next.

It was thus that I was able to take my degree of Licenciee-es-Lettres

(with the distinction of having been placed first in Mediacval

History), and at the same time the "auditorat" of Scholastic

Philosophy.

While in Paris, I came into

touch with the Christian Democratic movement, through Marc Sangnier

and his "Jeune Republique," and thus heard of the work

Don Sturzo was doing in Italy as leader of a great Christian-Democratic

party. I had been back in London only a few months when I heard

of his arrival in England, I was then living precariously as

a free-lance journalist (supplemented by keeping the accounts

for a private hotel), and wrote to ask if I might interview him.

This was the beginning of a collaboration that lasted till his

departure for the States in 1940, and which indeed still continues.

I became his interpreter while he still knew no English, then

the translator of his books and articles, his associate in various

enterprises of which I shall speak later. Contact with such a

mind was in itself an education, but I owe to him also a constant

and precious guidance in my own work. It was with his encouragement,

assisted by his criticism, that I produced my own first book,

the reconstruction of the later life of Dante in the form of

a novel, Ship Without Sails.

I had learned Italian in my

last year at school, and at once the Divine Comedy seized

my imagination, together with the figure of Dante himself. For

years, without and often against my will, a story that centered

round him wove itself in my mind, and whenever chance offered

I had read what I could find about him and his times. For long,

however, the task of writing on so great a theme seemed beyond

my powers. When at last I addressed myself to it, I was confirmed

in my leaning towards the form of a novel by the consideration

that most of his biographers, presenting conjecture as fact,

had written but fiction in disguise, and by the belief that through

the novelist's imaginative approach it might be possible to reconcile

apparently conflicting texts, and, paradoxically, to reach a

truer picture of him than by analytical research. (In this I

was justified: my conclusions as to the sequence of events in

his exile and his up till recently much questioned sojourn in

Paris, have since been independently put forward by one of the

leading Italian Dante scholars of the day.)

In all, the book was the work

of seven years, interrupted indeed by translations and articles.

Each year my summer vacation was spent in tracing Dante's wandering

steps across Italy, climbing to the almost inaccessible castles

that had harboured him, visiting the lovely cities associated

with his name Florence, Verona, Rome, Ravenna. The name

Ship Without Sails has a two-fold reference. Dante speaks

of himself as "a ship without sails, without rudder, driven

to divers ports and gulfs and shores," and it was in such

a ship that Lancelot (in whom Dante seems to have seen a symbol

of himself) came to such vision as might fall to sinful man in

the mystical quest of the Holy Grail.

The news that Ship Without

Sails had been accepted by a leading British publisher (Constable

& Co.) was cabled to me when I was staying in New Jersey,

on my first visit to my native country since I had left it as

a baby. (It was in 1929 still the Henry Ford era. Be it

confessed that I then felt a stranger, My discovery of the real

America was yet to come.)

My second book, Old Nurse,

appeared in 1936, published by Jonathan Cape. Translations (Soderini's

Leo XIII, Fanfani's Catholicism, Protestantism and

Capitalism, Don Sturzo's Cycle of Creation), lectures

and review-articlcs occupied the intervening years. Dante remained

my special theme. A collection of "New Dante Studies,"

indeed, lost its hope of present publication through the outbreak

of war, and a like fate befell my play, "Abelard" on

which both Mr. Robert Speaight and Mr. Martin Brown lookcd with

favour, promising production when a propitious moment came.

In the meantime, my association

with Don Sturzo had brought me ever more closely in touch with

the Christian Democratic movement. Towards the end of 1936 I

was one of the founders of the "People & Freedom"

group in London (taking its name from the mediaeval slogan, revived

by Savonarola's followers), with Mrs. Virginia Crawford as Chairman.

(She had been a favorite disciple of Cardinal Manning.) In 1938,

we founded a paper, People & Freedom, first a quarterly,

then a monthly, of which I am still editor, and in 1939, with

Don Sturzo's help, we brought out a book For Democracy,

with Burns, Oates & Washbourne, in which leading Catholic

sociologists of six countries trace the growth and basic principles

of dcmocracy from Greece and Rome to the problems of to-day and

the immediate to-morrow. My own share was the Introduction: What

we Mean by Democracy.") It has been recognised by competent

critics as a really important Catholic contribution to sound

political thought.

Such and kindred activities

(such as the organisation of the British Committee for Civil

and Religious Peace in Spain, and of the International Christian

Democratic Union), which have become more exacting since the

war, have limited my literary output. But a writer cannot live

in an ivory tower without spiritual impoverishment, and I believe

that this varied and practical experience will bear fruit when-as

I hope-a time comes fof me to turn single-heartedly to creative

work.

Originally published by

Walter Romig in The Book of Catholic Authors Volume Three,

copyright 1945

|

|